Collected works and novels

The beginnings and the first collections

Bruno Ginanni Corradini’s first poetic experiments are precocious and date back to 1910, such as the lyric I vecchi (The Old Men), the poem that shocked and outraged the inhabitants of his cherished Ravenna, who was old and immobile just like the ancient city. The scandal was provoked by these verses:

“Sacred old men, muted prophets of decay,

exhausted old men, pale spectres of eternity,

we beseech you old men, finish, we promise you

a beautiful funeral, hymns, fanfares, all will come,

They’ll cover your grave with flowers, and weep;

we beseech you old men, finish, old men, DEAD!”

Abusing the old was, at the time, a kind of watchword of the futurist literary avant-garde and this poetry piece could be linked to what would then become the theories of Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, founder of Futurism, who in order to guarantee a brighter future, had to defeat the cities of Podagra and Paralysis.

The very first production of Bruno Corra has been partially lost. A few titles mentioned in the correspondence between Marinetti and the musician Pratella remain as evidence. The first official publications appeared in the literary magazines ‘Il Centauro’ and ‘La Rivista’ in 1912, 1913.

It is also interesting to note, in this early period, the preference for critical-lyric reflections, i.e. lyrical digressions stimulated and developed by a critical cue as in E. Thovez’s Il pastore, il gregge e la zampogna, or Chantecler. (Lyrical Interpretation) of 1912.

Most of these early works were later republished in the poetic collection Con mani di vetro (With Glass Hands) of 1915, which also contains the first so-called ‘synthetic’ novels, i.e. ‘without preparatory chapters, without filler passages, without idle details, without clichés, just the essentials’. Among the best known are Biographical Notes of Lapa Bambi. The protagonist, a fat, extremely intelligent but apparently stupid woman, called Potato by everyone, is an unhappy woman both in marriage and more so in life. It is because of this unhappiness that Lapa decides to kill herself, thus giving the author the opportunity to describe, for the first time, an example of a comic funeral, which would later be common to the Futurists, Surrealists and Dadaists.

Sam Dunn is Dead

The collection Con mani di vetro (With Glass Hands) also contains the novel considered to be the ‘milestone’ of Bruno Corra’s literary experience: Sam Dunn is Dead, written in 1914, later republished in 1917 and reissued in 1970. It is a surprising, futuristic novel that includes some of the typical elements of avant-garde literature and the Futurist literary current. The story is set in the near future, in the years between 1943 and 1952. It narrates the itinerary of the wise but skeptical Sam Dunn, a ‘superior’ man full of remarkable occult energies, capable of bizarre feats and abstraction during which he remains completely immobile. He is able, thanks to an enhancement of his mind reading faculties, to channel a beam of ‘magnetised energies’ into Paris that unleashes a general madness in the city’s inhabitants. The most normal people are unleashed into unparalleled eccentrics, for instance at one point all citizens are drawn by the indomitable desire to pinch the ladies’ buttocks. And it is precisely because of the buttocks of the swarthy waitress Rosa André that the author can say that ‘Sam Dunn is dead’. The protagonist is in fact cruelly beaten and killed by the back of the woman’s body. Sam Dunn is dead, but this

“will not avert the marvellous adventure that so many clues announce […] We live on a powder keg of fantasy that will not be long in bursting […] Everyone knows the few crazy lines he wrote in a few minutes before he died: I am a bizarre moment floating in the madness of existence. I sit in my armchair stunned and uncertain in the face of quietly living reality. NE I have an impression of vertigo that is not dangerous after all. I blow a match and light, by God, a good cigarette.”

Exemplary in its essentiality, the work is a true synthetic novel that ties together and unfolds motifs from the most fertile territories of Futurist fiction: the occult and the comic. Their mingling leads to the suggestion of the absurd that resists the ‘estrangement’ achieved by comedy, one laughs at something that surprises and arouses fear. Traces of another world that has its own inflexible and inexplicable rules emerge in the story. Sam Dunn is Dead is a novel founded on the idea that we live on a powder keg of fantasy that will not be long in erupting, and that will erupt precisely with that whimsical novel in which surrealism is present, even preponderant.

In 1919, Corra published another collection entitled Madrigali e grotteschi, which included Con mani di vetro (With Glass Hands) and other compositions, short stories and novels, subsequent to 1914. In these writings, as in those immediately following, he continued his linguistic and content experimentation, which also led him to try his hand at ‘parolibera’. In the immediate post-war period, two singular novels on love themes were published entitled Io ti amo, and La famiglia innamorata, which are significant of a new, original and futuristic interpretation of love. Increasingly involved in the Movement also politically, Corra published L’Isola dei Baci together with Marinetti and later I bevitori di Sangue dedicated to Mussolini.

The 1920s and the Departure from Futurism

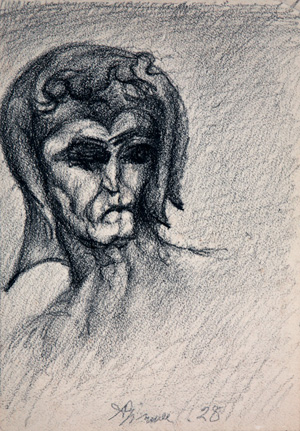

Already in the early 1920s, there was a gradual move away from the more extreme themes of avant-garde literature and a corresponding shift towards more traditional positions: the two novels of 1921, Santa Messalina and Femmina bionda, heralded the subsequent development of Bruno Corra’s literary activity.

In 1924, disappointed by the failure of the ‘Baracca’ project, a futurist circus and travelling theatre, Corra broke away from the Futurist Movement, but this decision did not interrupt his literary career. In fact, during the following years, he continued to publish numerous novels in the genre of escapist literature, enjoying considerable success with the public. He declares himself a ‘good writer’, entrusting this definition with a literary intent: his literature, which had long shown signs of a regression, had now shed its avant-garde guise to assume a more traditional role. These are written works based on the ability to alternate different expressive registers, which the author has acquired in the course of his varied readings.

They compromise historical novels, adventure novels, and mental health novels, all characterised by a common thread of narrative skill and a personal touch of the author, whose attention is drawn by events that are unusual, out of the ordinary and by uncommon cases of enigmatic characters who find themselves dropped into a conventional reality.

Among the various titles we can mention The Bull (1922), Why I Killed My Wife (1922), The Merry Adventure (1925), Sanya the Egyptian Wife (1927) and the collection The International Loves (1926). In the latter, having abandoned abuse, temerity, leapfrogging and slapstick, the author tries new ways to subvert literary tradition by writing short stories such as love stories set in artificially exotic scenarios. The parody of the language and stereotypes of the appendix novel produce effects of caustic irony. The return to more traditional themes and narrative structures is accompanied by the author’s obvious need for editorial success, the search for public approval and notoriety and, above all, the need for financial stability.

Dagli anni Trenta agli anni Cinquanta

From the 1930s to the 1950s

Common lines can be found, within the novels of this period, albeit different in genre and inspiration, such as the setting of the romance novels and the later novels of the 1930s, in which Corra brings to light the city-province dualism of his land of Romagna. The provincial environment, where authentic values are preserved, act as an antinomy to the city environment, where the worldly superficiality of the bourgeoisie prevails.

Romagna is an important element in Corra’s literature, and it is precisely this importance that explains Corra’s choice to narrate the legendary developments of a famous bandit from Romagna in one of his best-known and most appreciated novels, Il Passatore, (contact with cinema) first published in 1933, and later, in 1947, turned into the subject for a film. In narrating the tribulations of the bandit Stefano Pelloni, the author does not pay attention to historical facts, but on the contrary, thanks to the scarcity of information about the story, aided by imagination, he manages to create a true ‘Romagnolo state of mind’.

Corra’s copious production in these years includes novels but also comedies that often became successful theatre subjects or later, film subjects and screenplays.

Passing from one genre to another, Corra continued to be considered a successful writer until the early 1950s, but then he began to isolate himself more and more, closing himself off and being overcome by his obsessions, thus renouncing to storytelling and to an active presence in the Italian cultural scene.

Of some interest is the volume entitled, How to Become a Successful Writer published in 1956. Corra wrote this essay at the end of a career that could be described as successful even if erratic and in some ways inconsistent. At the beginning of the essay, the author openly declares his intention to write a

“… manual of the apprentice writer of small and medium calibre. A little written work for the use of those who aspire to be published and naturally paid … Those who have the light of genius in front of them will go their own way: towards glory, or towards the martyrdom of not being understood by their peers.”

This is the spoiled account of a disappointed writer who achieved success and financial comfort only by renouncing to his true artistic vocation.

Text by Lavinia Russo, supervision by Lucia Collarile.