The Last Years and Neo-Futurism

In the years leading up to the Second World War and during the war itself, Ginna abandoned all Futurist activity. He taught professional drawing in schools and, due to his expertise in the field, was employed as an official in the General Directorate of Cinema at the Ministry of Popular Culture.

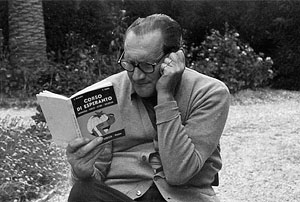

Subsequently, the years of Futurist clamour stretched into twenty years of silence and oblivion. In some ways Ginna’s design and creative drive had already undergone a turning point before the war, but the loss of his political ideals and friends, including the disintegration of the ideas he had cultivated in almost thirty years of activity in the Movement, caused a further estrangement of the artist from the Italian cultural scene. These are the years of introspection and solitude. After the war, Ginna worked as an official at the Ministry of Tourism and Performing Arts, and later at the General Directorate of Cinematography and of the Censorship Commission.

In the privacy of his studio, Ginna continued his incessant study of Steinerian opera. Picking up his old notebooks again and writing new ones, he began to jot down alchemy experiments and notes on art, with the objective, perhaps, of writing books that were never completed. These were writings on experimental painting techniques and philosophical thoughts applied to art, alternated with notes on healthcare and mathematical formulas to help win the lottery. He wrote about ‘Occult Painting’ and about the “History of the Spiritual Evolution of Painting”. He tirelessly revisited his explanation about his own art for others to understand and most certainly to clarify it for for himself as well.

During these years, for the most part, it was Ginna who painted. In fact, he has never stopped painting for himself, to advance in his own personal research. There are many, recurring themes, such as colour chords, musical themes, spirituality, animic portraits and wonderful landscapes. Since his years at the Academy, he has never completely abandoned figurative painting, as it best suited his last research in a form of spiritual art.

Neo-Futurism.

At the end of the 1950s, the publication of a number of critical texts and documentaries on the early years of Futurism, reawakened the interest of scholars and artists in the movement’s themes. Once again, from the whereabouts of the ghetto and oblivion in which, with rare exceptions, they had isolated themselves, the protagonists and witnesses of those years found themselves surprisingly legitimised to proclaim themselves Futurists in order to make their work known.

The revival of these themes provoked a new impetus in Ginna’s painting who, like many artists of his generation, began to revisit the themes addressed in the early years of Futurism. However, he did so in a new, more mindful way, as master of a style that would no longer be sought for, but that had to be conquered. In certain ways, his style is more Futurist today than it was at the time.

Reluctant to show and divulge his work, Arnaldo Ginna still remained in exile, after being deprived of the last remaining copy of Vita futurista, that had been entrusted to a scholar who was supposed to take care of its restoration but instead never returned it to its owner (only a few frames remain of the film, which was probably destroyed mainly due to the careless restoration).

What pained him the most, however, was to see his role as forerunner of abstractionism forgotten, a title he claimed with all his might.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

For this reason, in 1961 he published “Arnaldo Ginna. Un pioniere dell’Astrattismo”, with texts written by the philosopher Scaligero and by the gallery owner Sprovieri, in which his presence at the Futurist exhibition of 1914 is recalled.

The rediscovery of Arnaldo Ginna came about thanks to the work of Mario Verdone, who as a critic and cinema historian of the avant-garde, published his writings and some of his paintings between the years of 1967 and 1968.

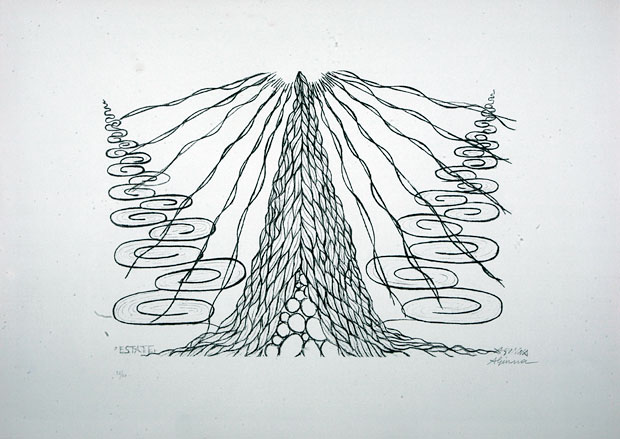

In 1969, another critic, Giuseppe Appella, curated a monographic exhibition in Macerata and then in Rome, in which approximately seventy drawings were exhibited for the first time from 1908 to 1967, finally testifying to the value of this artist’s work. Since then, his works began to participate in exhibitions on avant-garde art in Italy and abroad, and in the last years of his life, although always in a timid and isolated manner, Ginna resumed his public role as an artist. His very last production, the Magic Numbers, is dictated by a new philosophical theorisation, which is further developed in the Antipittura. Interior Expressions and the World without Colours and Forms, of the late 1960s.

In 1970, the text The Four Seasons was published, edited by G. De Turris. Lirics and Lithographs by Arnaldo Ginna, which was followed by the printing of the series of lithographs The Four Seasons in 1971, which can be considered the artist’s last work.

Three years after his death, in 1985, Mario Verdone dedicated a publication to him and a monographic exhibition to his hometown, Ravenna, as a perfect closure to a rich and important artistic career.

“Foto © Governatorato SCV, Direzione

dei Musei e dei Beni Culturali”

Text by Lucia Collarile.