Theoretical texts and manifestos

During the 1910s, the Ginanni Corradini brothers published three four-handed texts with the aim to divulge their thought.

Method, Vita Nova.

The first two texts, Metodo and Vita Nova, were practically published in anonymity, perhaps to avoid being penalized by their very young age. In this work, a practical method was developed, in order to be able to fully utilize the occult energies inherent in each individual: In brief, the message was that modern man can face their renewal and thus find complete spiritual intellectual and physical enlightment through the use of mental and physical exercises that drew on oriental disciplines.

Art of the future, painting of the future.

At the origin of the third publication, laid the discovery of nature as a vital element, referred to as the ‘subconscious primal force’. The liberation of this force was able to generate new artistic languages and thus new art. The Treatise was first published in March under the title Art of the Future, then republished the following year as ‘Art of the Future. Paradox”, and it may be considered one of the very first avant-garde works of the 20th century. It is a scientific dissertation in which, for the first time, art and science are placed on a common level and all art forms such as music, sculpture, painting, literature, theatre, architecture, including photography and cinematography, are examined using scientific methods, according to the view that ‘ the essence of the arts is one, the means of expression are varied’. Among the arts, music, from a scientific-artistic perspective, is the most complete creative expression.

Rome, private collection.

Futurist science. Futurist cinematography.

By this time, Ginna had already fully joined the Futurist Movement. His production of theoretical essays continued and merged into the publication of several manifestos: in 1916, from the pages of L’Italia futurista he launched the manifesto La scienza futurista (Futurist Science), and co-signed it with Corra, Chiti, Settimelli, Carli, Mara and Nannetti. This was a rare publication that intended to abolish science with with a capital S and proposed

“a bold, futurist exploratory science, a highly sensitive science […] influenced by remote, fragmentary, and contradictory intuitions, happy to discover a truth that destroys the truth of the past, all soaked in the unknown.”

This manifesto, points out the feeling of revolt against positivism which becomes a state of awareness instead; a realism that remains unexplained and leaves the human being certain of their insecurities. It is precisely in the points which new psychic sciences and studies of occult energies are addressed, that the contribution of the Ginanni Corradini brothers to the manifesto is most identifiable.

Also in 1916, he co-signed the manifesto La Cinematografia Futurista (Futurist Cinematography), with Marinetti, Corra, Settimelli and Chiti, which theorized and formalised all the artistic possibilities offered by the new cinematic means of expression and called for the

“liberation of cinema – a means of expression best suited to the multi-sensitivity of a Futurist artist – in order to make it the ideal instrument of a new art immensely broader and more deft than all existing ones.”

Ginna had already put these theories into practice in some cinematographic experiments carried out with Corra around 1912 by painting directly on blank film, and in experiments described in the text by Bruno Corradini entitled Chromatic Music of 1912. Marinetti entrusted him with the organization and production of the 1916 film Vita futurista (Futurist Life), which, besides perhaps being the first avant-garde film in the history of cinema, served as a preparatory experience for the drafting of the subsequent manifesto. Many of the ideas proposed by this document were later adopted by the experimental research that was conducted on cinema by the European avant-garde.

Futurist furniture. The Scienzarte

Also in 1916, Ginna wrote the article in ‘Futurismo’ entitled, ”Il primo mobilizio italiano futurista” (The First Italian Futurist Furniture), essentially, a manifesto in which he laid out the scientific foundations for the construction of furniture and furnishings to meet the needs of modern man according to the character of Sant’Elia’s new futurist architecture.

In the following years, especially since the end of the 1920s and onwards, his activity concentrated on his work as critic and theorist of art, especially of film and radio. Ginna wrote articles from the pages of L’Impero, Oggi e Domani and Futurismo, in which he presented new ideas about art and art criticism. His texts regarding Scienzarte, a discipline he theorized according to philosophical axioms, were very interesting and enabled scientific results to be achieved only with the use of artistic means.

Future Man. The futurist naturism manifesto. The presentist idea.

In 1933, Ginna published The Future Man with a preface by Marinetti. It is an essay with a strong political connotation, which began with youthful theorisations and then moved towards differing solutions. It introduced the glorification of the futurist human being, a connoisseur of the occult energies that can regulate existence and be transformed into dynamic forces by man. The futurist human being is embodied in Marinetti and Mussolini and the text is clearly aimed at re-establishing the link between Futurism and Fascism, at a time when the movement needed to reaffirm its common origins and aims.

Once again, in partnership with Marinetti, he wrote the Manifesto of Futurist Naturism, introduced at the First Futurist Naturism Convention held in Milan from 29 September to 6 October 1934. The subject of Naturism had interested the Ginanni Corradini brothers until 1910. It is present in their early theoretical writings and will have interesting developments in the Movement. In 1934, Ginna published Il Nuovo, A bimonthly edition of Fascist and Futurist Human Energetics. In Ginna’s naturist thought, one begins to see a glimpse of a clear change of direction compared to the theories of his youth. Male sports, all kinds of cars, speed and the praise of war become part of his concept of naturist and futurist man, essentially, a form of naturism adapted to the needs of the time.

Another publication, entitled: L’Idea Presentista (The Presentist Idea) of 1937, by Ginna, is at the same level, in which he exalts the capacity inherent in each of us (but exploited only by a few that are gifted with special energies) to predict the future through nature and therefore Naturism.

Cinematography. The Anti-Painting

Ginna’s last work and theoretical text published as a Futurist is, not surprisingly, the manifesto La Cinematografia (Cinematography), co-signed with Marinetti in 1938, in which, as was the practice, he claims the role of anticipator and ‘updates’ the text of the 1916 manifesto with the technical discoveries that took place in the following twenty years regarding sound, colour, new filming and projection machines.

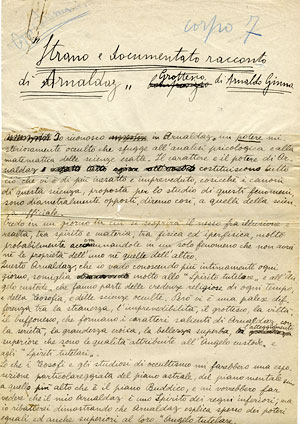

Although he no longer published any works and despite his gradual departure from the Italian cultural scene, Ginna continued to write theoretical and philosophical essays. His notebooks are full of writings that are frequently undated, although, to a great extent, they can be traced back to the 1940s and 1950s. Some of these are undoubtedly starting points for other publications, dealing with topics that are important and fundamental for the understanding of his image as an artist and art theorist , but that were never completed, for example, the History of Spiritual Evolution in Painting, Painting of the Invisible, Alchemy and more recently, at the end of the 1960s, Antipittura. Inner expressions and the world without colour and form, in which Ginna declares himself beyond painting and beyond artistic expression itself, claiming a sort of absolute supersensitive sphere, the logical evolution of the supersensitive in the so-called abstract painting.

Text by Lucia Collarile.