Futurist Ginna

In 1909, the first great European avant-garde movement called Futurism was born, founded by Filippo Tommaso Marinetti. Arnaldo and Bruno Ginanni Corradini recognised themselves in many of the theories advocated by the movement and, during its most heroic phase, they became protagonists in their own way. The musician, Francesco Balilla Pratella from Romagna, who joined the Movement in 1910, was the middleman between the two Corradini brothers and Marinetti was their friend. It was he who organised the official meeting with the Futurist general staff in Milan around 1912. The Futurists were already familiar with the theories of the Arte dell’Avvenire, and Boccioni, must have been particularly impressed by them as, in these same years, he explored the themes of moods in painting. This is how Ginna describes the historic meeting:

“We set off for Milan to meet Marinetti in the Casa Rossa in Corso Venezia. We rang the doorbell, Carlo Carrà opened the door and led us to the studio lounge where he introduced us Marinetti, Boccioni and Russolo. They had a long and heated discussion precisely on the topic of painting. While the Futurists held on to the concept of dynamics, we were convinced (through the logic expressed in Arte dell’Avvenire) that one could also make music with colours, in accordance with the music of sounds…”

In the Futurist circles, the theories of the Ginanni Corradini brothers certainly provoked interest but also a great deal of mistrust and therefore the entry of the two artists into the movement was not easy and unpainful, especially for Ginna.

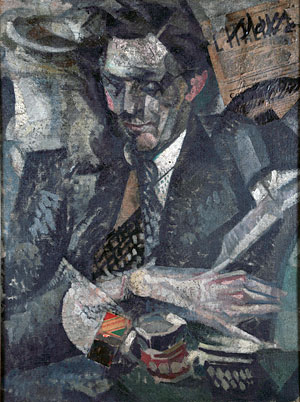

In 1914, the controversy intensified with his participation in the Free Futurist Exhibition in Rome. Ginna exhibited six works that were revolutionary in their own way but were considered ‘literary’ in contrast to the Futurist idea of freeing art from cerebral thinking forever. Therefore, while some Futurists such as Prampolini accused him of not being a proper Futurist, Boccioni defended his very personal vision of art, exalting its musical aspect.

Despite the controversy, the artist fully entered Futurism with this exhibition, even though the actual induction into the Movement was officiated by the painter Giacomo Balla, who gave him and his brother their two Futurist pseudonyms: Ginna (by combining Ginanni and “ginnastica” gymnastics) and Corra (by combining Corradini and “corsa” race), with which they would autograph their works until the end of their careers.

Rome, private collection.

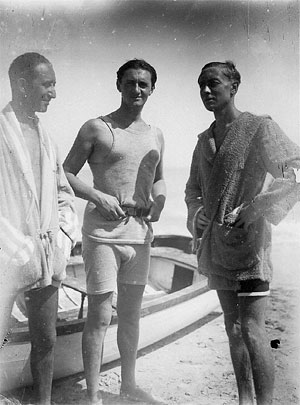

Photograph by Pietro Zigrossi. © Vatican Museums Photographic Archive.

The Second Florentine Futurism.

At the end of 1912, Ginna, and his brother Bruno, moved to Florence where he enrolled at the Royal Institute of Fine Arts and graduated in 1914. Here, he regularly visited and became acquainted with the literary and artistic circles of the Tuscan capital. It was precisely in the year 1912 that the Corradini brothers, Emilio Settimelli and Mario Carli, began their collaboration. Together, they founded the magazine Il Centauro and began the publication of La Rivista, the following year. A group of artists, writers and intellectuals started to take shape around them, that would give life to the so-called ‘second Florentine futurism’, later named ‘blue patrol’.

Futurist Italy.

The fulcrum, around which the whole Florentine group revolved, was the editorial staff of the magazine L’Italia Futurista, founded in 1916 and edited in turn by Corra, Settimelli, and Ginna and finally, by Primo Conti in 1918. The magazine was extremely innovative in terms of layout, typography, and graphics. It published important manifestos, theatrical syntheses, words in freedom and Parolibere tables, novels and prose of a surreal content, as well as articles on nationalism and war also written by Futurists stationed on the frontline. Marinetti’s presence was consistent, especially in political writings, and this demonstrated his total support for the initiative.

Ginna took an active part in the editorial staff of the magazine and in the development of its editorial line, and also wrote numerous articles on important topics related to scientific matters, occultism and literary criticism, and published short stories and plays, including theoretical texts, illustrated literary texts, and wrote phonetic poetry. Together with Corra, Chiti, Settimelli, Carli, Mara, and Nannetti, from the pages of Futurist Italy, he launched the manifesto La scienza futurista (Futurist Science), in which his influence can be noticed especially when he addressed the new psychic sciences and the study of occult forces. His creativity was also positively stimulated by his sentimental bond with the poetess Maria Crisi, who took on the artistic pseudonym of Maria Ginanni when they married. It is she who founded and directed ‘I libri di Valore’ (The Valuable Books) series of Futurist Italy editions.

As an editor, she published seven volumes, all containing covers designed by her husband, including Pittura dell’Avvenire in 1917, the theoretical text written by Ginna in an attempt to simplify and focus on the theories of Arte dell’Avvenire (Futurist Art) and pictorial art alone. The preface to this text written by Bruno Corra is fundamental. For the first time, Bruno validates the different souls that compose Futurist painting and would develop autonomously in the years between the two wars:

in the timespan of ten years the plastic dynamism of Boccioni, the imaginative research of Balla and Depero, the synthetic reconstructions and unreal visions of Arnaldo Ginna and Leonardo Dudreville would come to life.

Futurist furniture

In an article published in the l’Italia Futurista edition of 1916 and entitled Primo mobilizio italiano futurista (First Italian Futurist Furniture), Ginna reveals that he designed and built luxury furniture inspired by ultramodernism criteria, such as hygiene, elegance and synthetic emotion as advocated by the Futurist architect Sant’Elia.

“The furnishing of a house, a ‘restaurant’, a hotel must have character, what I mean is that each room must have a physiognomy that goes along with what one wants to accomplish … It seems to me that in this way art finds a worthy task to fulfil. Art is introduced into our intimate life, attitudes and needs. It seems to me that the introduction of this high level of refinement; a new and all-Italian elegance; of care, well-being, cheerfulness and optimism in life is a worthy task.”

Vita futurista (Futurist Life)

The most significant experience of this period for Arnaldo Ginna was the making of the film Vita futurista, the first futurist film and probably the first avant-garde film in the history of cinema. Thanks to the experience on film acquired during the years of youthful experimentation with his brother Bruno, Marinetti decided to entrust him with the organisation and realisation of the project. The film for Ginna was a considerable physical and financial commitment, soley responsible for the project, given that the futurists involved were often undisciplined, lazy and sleepy; clearly, more engaged in goliardic endeavors rather than in such important work that would soon become the matrix of practically all subsequent European avant-garde cinema.

Also in 1916, the manifesto La cinematografia futurista (Futurist Cinematography) was published, signed by Marinetti, Ginna, Corra, Settimelli and Chiti, in which all the artistic possibilities given by the new expressive medium of cinema were theorised and made official. Many of the ideas proposed by this manifesto would later be adopted by the experimental research on cinema conducted by the European avant-garde. At the end of 1918, Ginna lived in Milan together with Maria Ginanni who, after she had ended the adventure of Futurist Italy, now directed a literature series for Edizioni Facchi. Among his many activities, Ginna also devoted himself to illustrating literary texts: he had already tried his hand at a pre-Futurist work by Gian Pietro Lucini: La nuova Carmagnola from Revolverate, published by Edizioni Futuriste di Poesia in 1909. Then, as previously mentioned, he would dedicate himself to illustration throughout the period of Futurist Italy. In 1919, Corra’s volume Madrigali Grotteschi was published, for which Ginna made illustrations in The Funeral of Lapa Bambi and Sam Dunn is Dead. The same year, Ginna published a collection entitled Le locomotive con le calze (Locomotives with Stockings), which gathered some of the stories published in the pages of L’Italia Futurista.

Again in 1919, Ginna took part in the Grande Esposizione Nazionale Futurista, in Milan and then in Genoa and Florence, where he exhibited two paintings as well as a pillow display.

Ginna’s last participation in a Futurist exhibition took place in 1922, at the International Futurist Exhibition, in the Turin Winter Club where he displayed three works.

Futurist Ginna in Rome.

When his marriage to Maria Crisi ended, Ginna moved to Rome, a stone’s throw from Casa Balla, which in those years, became one of the meeting points of Roman Futurism. In the following years, he remarried to Maria Bachetoni with whom he had a son.

In these years, his work primarily focused on collaborations with the editorial offices of newspapers and magazines connected with the Futurist Movement and directed by his friends and collaborators from the Florentine period: from 1926 with L’Impero (The Empire) and from 1930 with Oggi e Domani (Today and Tomorrow) and Futurismo. At the beginning of his collaboration, Ginna still published short stories, some illustrations and critical texts, but from 1929 onwards, he mainly dealt with cinema, film critics and cinesonoro (film sound).

In the 1930s, once again, Ginna undertook new activities within Futurism. This was perhaps a way of reaffirming his role as the Movement’s theorist and strengthening his ties with Marinetti at a time of great tensions also due to his increasingly political implications.

In fact, in 1933, Marinetti published L’uomo Futuro (the Future Man), in whose character he reiterates the importance of the artist’s activities. This significant recognition, by the founder of Futurism, was offered to his friend Ginna, in exchange for a text with strong political undertones, that re-established the link between Futurism and Fascism by reaffirming the common origins and aims. Once again, alongside Marinetti he wrote the Manifesto of Futurist Naturism, that he presented at the First Futurist Naturism Convention held in Milan from 29 September to 6 October, 1934. Ginna also edited Il Nuovo. Fascist and Futurist human energetics, fortnightly.

In Ginna’s naturist thinking there is a clear change of objectives from the theories of his youth. A naturism adapted to the needs of the moment, such as virile sports, all kinds of machines, speed and the exaltation of war, became part of his concept of the naturist and futurist man.

At par is another publication by Ginna: L’Idea Presentista (The Presentist Idea), in which he praises the human capacity to predict the future through nature and therefore naturism.

The last work Ginna completed as a Futurist before the war was, not surprisingly, the manifesto La Cinematografia (The Cinematography), signed with Marinetti in 1938, in which, as was the practice at the time, the role of visionaries was asserted and the text of the 1916 manifesto was ‘updated’ with the technical discoveries that took place in the twenty years that followed regarding sound, colour, new filming and projection machines.

His activity in the Movement ended at the turn of the 1930s. The war and the loss of ideals and of his friends led him to an almost total parting from the post-war Italian cultural scene. It was only at the end of the 1960s, that, thanks to a gradual rediscovery of Futurism and its protagonists by critics and historians, Ginna, albeit in a shy and secluded manner, resumed his role as an artist and began to exhibit paintings again, surprisingly even new ones, in a style that can be defined as Neo-Futurist.

Text by Lucia Collarile